Startup Business Model and Pricing

A deep dive into the most successful startup business models and pricing strategies—what works, why it works, and how to apply it. Learn from billion-dollar companies and top YC startups to craft a scalable, defensible, and profitable startup.

Most founders get frustrated when investors won't fund them or their business won't grow, and they're not sure why. Usually, it's because they're not using a proven business model. They're trying to reinvent the wheel when they should just copy what works.

There are only a handful of business models responsible for nearly all billion-dollar companies. Rather than trying to be clever, you should pick one of these proven models and focus on innovating your product instead.

The 9 Business Models That Build Billion-Dollar Companies

- SaaS - Cloud-based subscription software

- Transactional - Facilitate transactions and take a cut (usually fintech)

- Marketplace - Facilitate transactions between buyers and sellers

- Hard-tech - Lots of technical risk and long time horizons

- Usage-based - Pay-as-you-go based on consumption

- Enterprise - Sell large contracts to huge companies

- Advertising - Sell ads to monetize free users

- E-commerce - Sell products online

- Bio - Science-based tech companies

Each of these models has specific metrics that matter most, key takeaways, and similar companies you can learn from. But rather than diving deep into each one, let's look at what we can learn from the companies that actually succeeded.

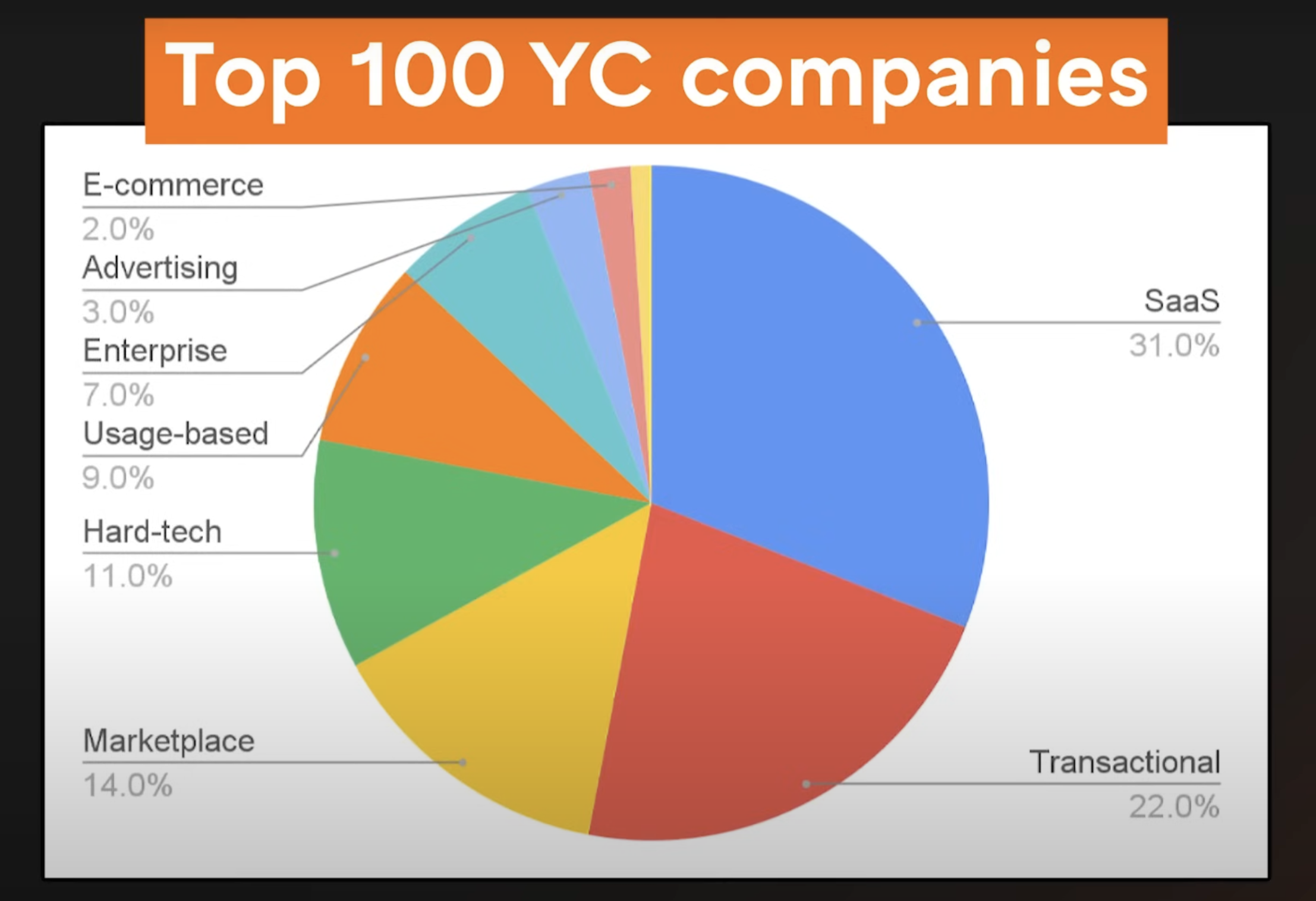

What the Top 100 YC Companies Teach Us

The YC Top 100 companies list reveals some fascinating patterns about which business models actually work. But first, it's important to understand the power law effect: the biggest winners far outperform all other businesses by orders of magnitude.

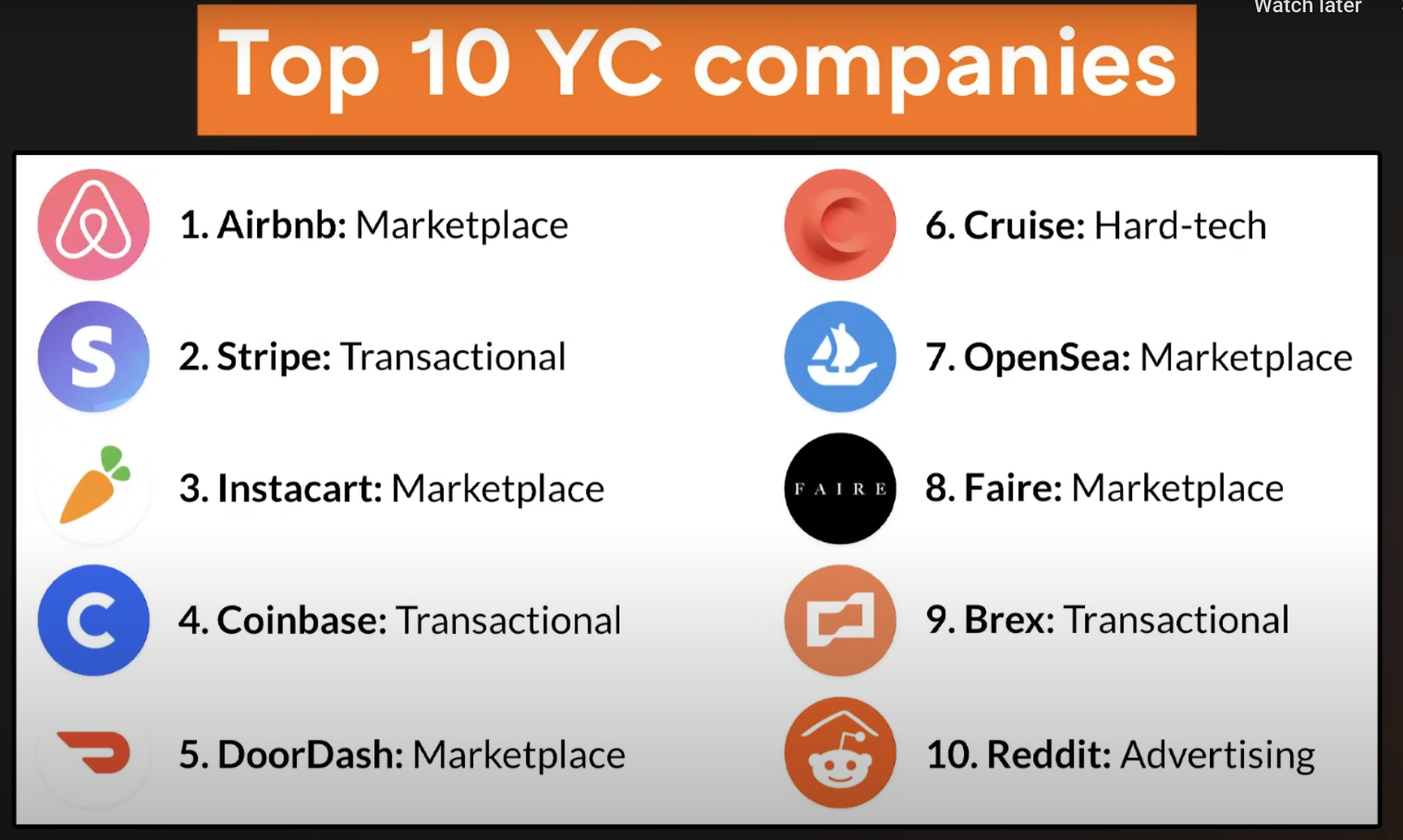

This is true for the YC Top 100 as well. Fifty percent of the overall value of the top 100 companies comes from just the top 10.

Looking at these top 10 companies, some patterns emerge that are worth paying attention to.

Marketplaces Dominate

Five of the top 10 YC companies are marketplaces: Airbnb, Instacart, DoorDash, OpenSea, and Fair. This is remarkable because marketplaces only make up 14% of the top 100 companies, but they create 30% of the overall value.

Marketplaces are most likely to build winner-take-all companies. They tend to become so dominant in their industry that there's little room for competitors. Once they hit their inflection point, they get massive network effects where each new user increases the value for everybody else.

Think about it: if you want to rent a place short-term, you go to Airbnb because that's where all the inventory is. If you want to buy or sell NFTs, you go to OpenSea because that's where everyone is. That's how these become the big winners.

The catch is that marketplaces are incredibly tough to get off the ground. They have a chicken-and-egg problem where you need both supply and demand to exist simultaneously. But once they work, they become nearly unstoppable.

Transactional Businesses Outperform

Three of the top 10 are transactional businesses: Stripe, Coinbase, and Brex. Transactional businesses far outperform because they're directly in the flow of funds. They're the platform that money flows through, making it very easy for them to take their cut.

Transactional companies are 22% of the top 100 companies but create 29% of the overall value. This is because they're as close to the transaction as possible.

If you're a company like Stripe that literally processes money for companies, or Brex that is the corporate card they use to spend money, then you're directly in that flow of funds, so get as close to the transaction as possible.

Because they're so close to the transaction, they often become critical infrastructure for other companies. They solve a top-three problem for their customers. You can imagine if you use Stripe as your primary method to get paid from your customers—the thought of ripping that out sounds terrible. That's why these transactional businesses become so dominant.

SaaS Companies Are Reliable

SaaS businesses are most likely to make the top 100 list. Thirty-one of the YC top 100 companies are SaaS businesses—nearly a third. This is because recurring revenue makes them great businesses.

Customers keep paying them every month or every year until they explicitly say to stop. This creates predictable revenue that allows them to compound and grow their business.

Advertising Is Rare

Very few advertising businesses become big winners. Only 3% of the top 100 companies use an advertising business model as their primary way to make money.

This may be surprising because we're so familiar with companies like Google, Facebook, and Twitter. But advertising businesses need organic virality to win. They need to catch lightning in a bottle and become the hub where all users go to hang out.

When that happens, they get really strong network effects. People go to hang out on Reddit and form communities there because that's where everybody else is. People go to Twitch to watch live streams because that's where all the streamers are.

You should not use ads as your primary business model unless you expect to be a top 10 site on the internet. Otherwise, it's too hard to monetize and build huge scale.

What's Missing from the Top 100

It's just as revealing to look at what's not in the top 100:

Services/Consulting businesses - Non-recurring revenue, scale with people, low margins.

Affiliate businesses - Too far away from the transaction. Multiple things have to happen before you get paid.

Hardware businesses - Require lots of capital, have low margins.

Businesses built on other platforms - Too much platform risk. If your business starts to work, it's in the platform's interest to shut you down and capture that revenue for themselves.

The Power of Recurring Revenue

Recurring revenue consistently creates winners because it's highly predictable. Once a customer has committed to pay, they're going to continue paying until they explicitly say they want to stop.

It also results in higher customer lifetime values versus one-off transactions and lower customer acquisition costs. You don't have to keep reacquiring customers over and over.

But recurring revenue only works when you have strong retention. You need to keep delivering value over and over again, otherwise your customers will churn and stop paying.

The math is brutal. If you have 95% monthly retention, that means 5% of your customers churn every month. If you start with 100 customers, by the end of the year you'll only have 54 customers. You lose 46 customers in a year and need to get 46 new customers just to break even.

If you have 90% monthly retention instead, you'll only have 28 customers at the end of the year. That five percent difference can be the difference between life and death for a startup.

Building Defensible Moats

The biggest winners are built with moats:

Network effects - Many marketplaces have this, where each new user increases the value for everyone else.

Lock-in and high switching costs - We see this with transactional businesses like Stripe. If you're the primary way people accept money, they're not going to switch off of you.

Technical innovation - Companies like Cruise (self-driving) and Boom (supersonic jets). It takes years of difficult technical development just to catch up.

Higher margins and better unit economics - Companies like DoorDash and Instacart have reached economies of scale that new entrants can't compete with.

Organic distribution - If you can get users for free through virality or word of mouth, you can dominate your market.

The Best Business Models

The best businesses:

- Generate recurring revenue

- Have high retention

- Build defensible moats

- Are close to the transaction

- Scale with software, not people

- Are proven and familiar to customers

Focus on innovating your product. That's what should be new. Copy your business model from one of these proven winners.

Pricing as a Learning Tool

Pricing is not just about making money—it's a tool to help you learn faster. It can teach you who wants your product, how much they want it, how much value your product provides, and which channels you can afford to use to acquire customers.

Here are five pricing insights from the top YC companies:

1. You Should Charge

This is the most common mistake founders make. They're afraid to charge because they're afraid customers will say no, walk away, or use their competitors' product.

But charging is actually one of the most effective ways to learn important things about your business. It teaches you whether your users are willing to pay at all. It's often binary—either they're willing to open their wallet or they don't see enough value to overcome that hurdle.

It can also teach you which users are most willing to pay. If you're trying to decide between customer segment A or B, seeing which one is most excited to pay gives you good signal on who wants your product more.

Stripe is a great example. In the early days, while most competitors were charging around 3% per transaction, Stripe decided to charge 5%—nearly double. They wanted to test how much value customers saw in things like one-click signup and detailed developer API documentation.

Rather than trying to undercut the competition, they set a high bar for themselves to prove they had built enough value into their product.

2. Price on Value, Not Cost

Founders often start with cost-plus pricing. They look at how much it costs to serve a customer and add an amount on top. I don't recommend this because it ignores the full value that customers see in your product.

The difference between your cost and your price is your margin. The difference between your price and the value customers see is your opportunity to raise prices and capture more of that perceived value.

If your cost is higher than your price, you have negative margins and can't scale. If your price is higher than the value customers see, they won't buy from you.

How do you find your value? Talk to your users. Ask them about the problem you solve and get them to articulate the value to you. Ask: "What problem were you hoping our product could solve for you?"

Their response is usually one of four things:

- Make more money

- Reduce costs

- Move faster

- Avoid risk

Another way is to keep incrementally raising prices until you get pushback. The ideal price is when customers complain but they still pay. If they accept immediately, you're probably pricing too low.

3. Most Startups Are Undercharging

You almost certainly are. Lower prices are not a sustainable advantage. Sometimes founders say, "Our product is just like our large competitor except ours is cheaper." That's not a way to build a winner. It just means your large competitor can underprice you even lower until they put you out of business.

When you charge more, you get higher margins and can build a bigger moat. You can pay more to acquire customers, which means you can acquire all the customers before your competitors do.

Pricing also implies value. When customers evaluate your product, they don't have many signals on how valuable it is, but price is one of the primary ones. If your price is lower than competitors, customers might assume your product is less valuable.

Raising prices is actually the easiest way to grow revenue. If you have 1,000 customers and want to double revenue, it's much easier to double your price than to get 1,000 more customers.

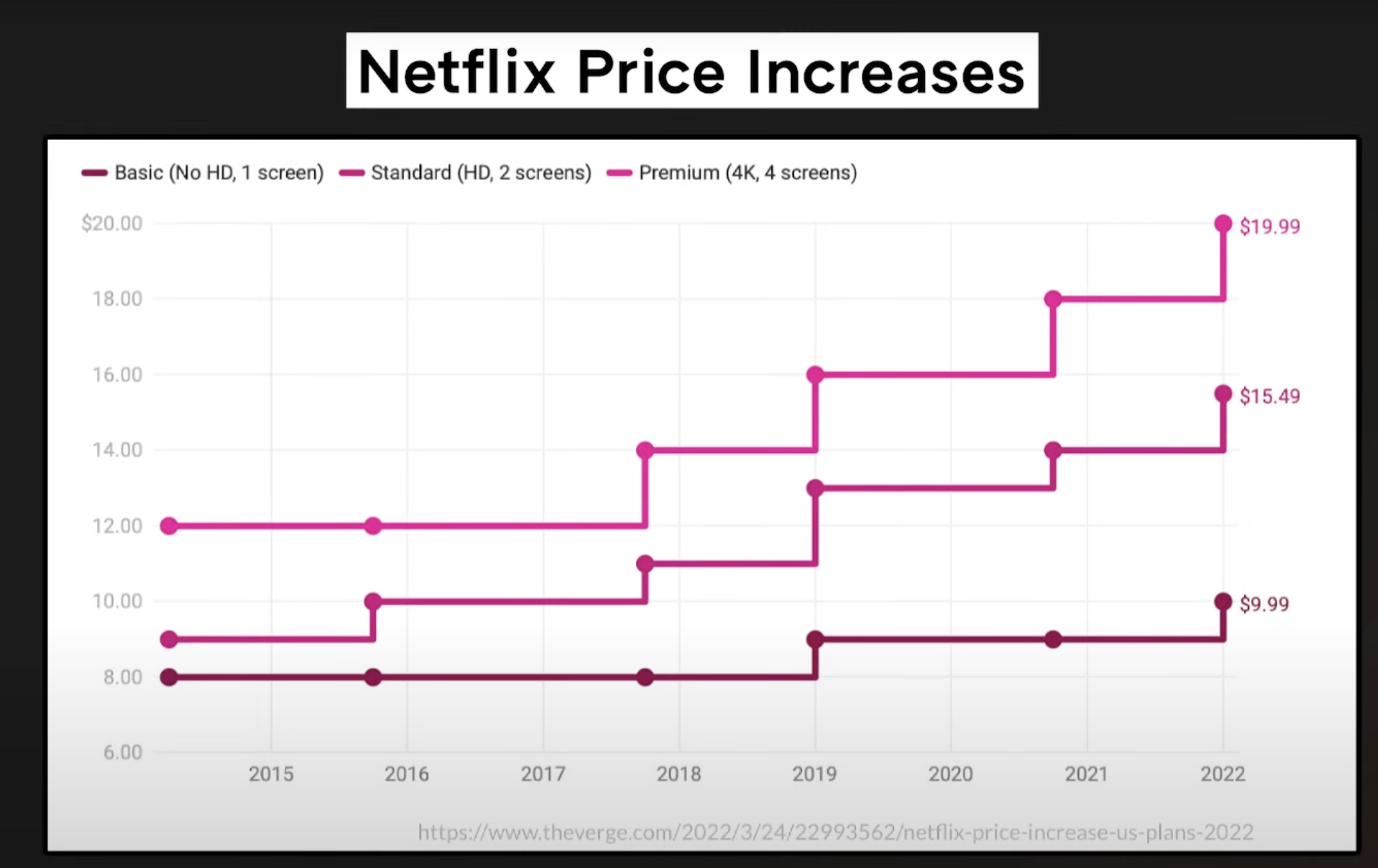

4. Pricing Isn't Permanent

This is another common fear. Founders think they have to nail pricing the first time or they'll lose customers forever. But pricing is relatively painless to increase over time.

You can exclude existing customers by letting them keep their current pricing and only raising prices for new customers. Or you can give advance notice that you plan to raise prices.

Netflix is a great example. This chart shows their price increases over the last seven years. They're not shy about raising prices on their customers. Netflix has 221 million paid subscribers and has figured out how to raise prices because that's the easiest way to grow revenue.

If Netflix can figure out how to increase prices on 221 million customers, you should be able to do it on your handful of early customers.

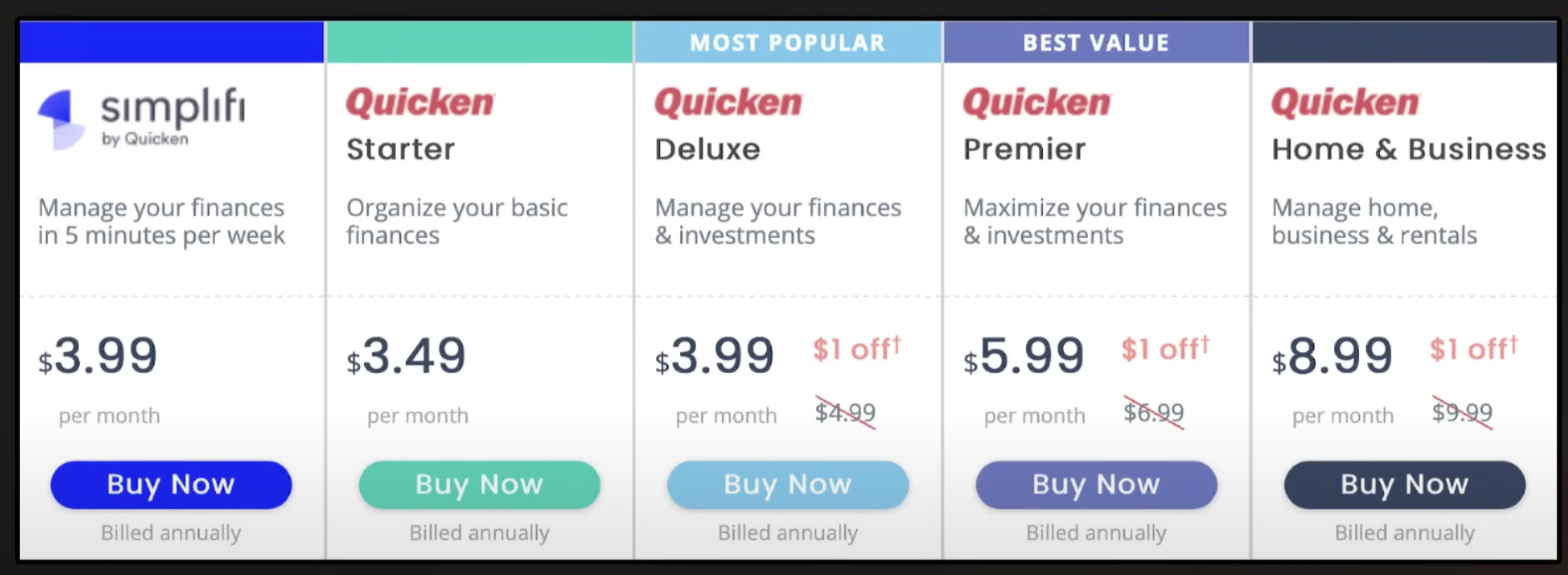

5. Keep It Simple

This is an example of a pricing page for Quicken. It's very complex—five different buy buttons, multiple prices, crossed-out prices, one-dollar-off symbols. It's really complicated to figure out which plan you should choose, which likely results in decreased conversion rates.

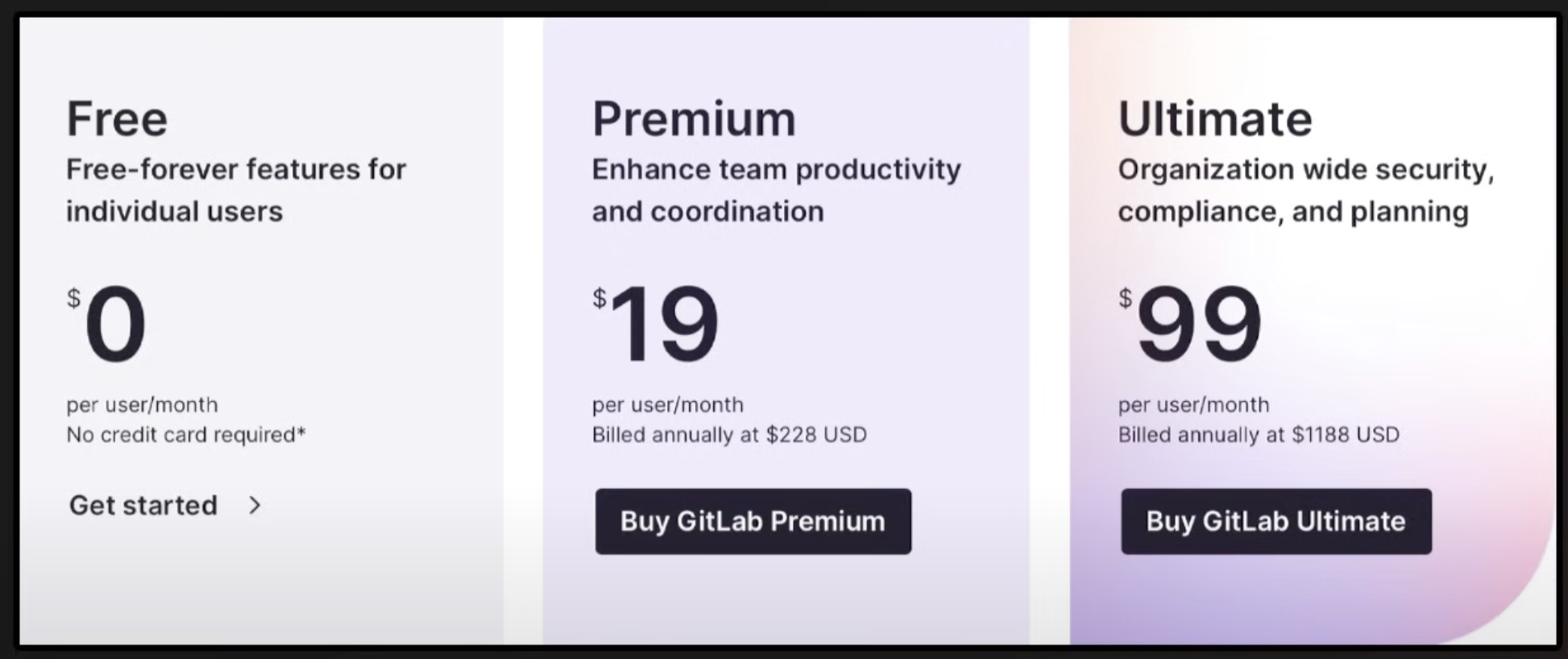

On the flip side, here's GitLab with three very clear, simple plans. Their pricing page is not going to be the thing that adds friction and prevents customers from signing up.

The Story of Segment

Segment helps companies capture and use their customer data. When they started, they were a couple of engineers not used to paying for products themselves, so they thought they had to give their product away for free.

When they wanted to raise money from investors, they decided maybe they should charge customers money to show revenue growth. Sheepishly, they reached out to all their free customers and told them they were going to start charging $10 per month ($120 per year).

Surprisingly, their customers responded with messages like, "I hope you would charge me more than that, otherwise I'm worried about keeping my customer data with you." The low price was signaling to customers that maybe their product was invaluable or couldn't be trusted in the long term.

To grow even more, they hired a sales advisor who told them, "You should not be charging $120 a year. You should be charging $120,000 per year." This scared them—it was unfathomable that anybody would pay $120,000 per year for their product.

When they went into their first sales meeting with the advisor, he told them, "If you don't tell this customer that your price is $120,000, then I quit as your sales advisor."

At the end of the meeting when it came time to talk price, the customer said, "So how much is it?" The CEO got really red and nervous and said, "$120,000." The customer responded, "How about $12,000?" They ultimately agreed on $18,000.

While they didn't get the 1000x price increase, they were able to increase their price 150 times from $120 a year to $18,000 a year. It wouldn't have happened if they didn't ask for the higher price.

They used this philosophy to continue growing their deal sizes all the way up to six figures and beyond, ultimately leading to their acquisition by Twilio for more than $3 billion.

Summary

The five key pricing insights:

- You should charge - It's the most effective way to learn about your business

- Price on value, not cost - Don't ignore the full value customers see in your product

- Most startups are undercharging - You probably are too

- Pricing isn't permanent - Don't fear getting it right the first time

- Keep it simple - Don't add complexity that creates friction

The key insight is that business models and pricing are not things to be clever about. Copy proven models, charge what your product is worth, and focus your innovation on the product itself.

Notes

[1] Much of the business model breakdown is inspired by Y Combinator's Business Model Guide and talks from YC Partners, especially those given during Startup School.

[2] The observation that marketplaces and transactional businesses disproportionately create value comes from YC's internal analysis of their Top 100 companies, demonstrating the power of being close to the flow of money and capturing network effects.

[3] The insight on retention math (e.g., 90% monthly retention = 28% yearly) is a core YC concept to emphasize how even small churn adds up—and why retention is critical for recurring revenue models.

[4] "Price on value, not cost" and other pricing strategies are drawn from years of YC startup experience and founder mistakes, including stories from Stripe, Segment, and others who learned to charge more by understanding the real value their product delivered.

[5] The Segment pricing story is based on real founder anecdotes shared in YC office hours and public blog posts—illustrating how startup founders often begin with underconfidence in pricing and learn to adapt by listening to customers.